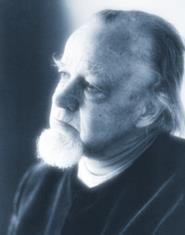

Here are my notes from a previous discussion from our Friday night series on How Should We Then Live? Chapter 5 continues the discussion on the Reformation, but focuses on the the impact of the Reformation on the relationship between government and its citizens.

People looking back 500 years later get bent out of shape that the Reformers had a lot of vestiges of their own era. I appreciate that Schaeffer points out that the political freedom that came from the ideas of the Reformation was a gradual change.

We cannot idolize the Reformation, because they were sinners saved by grace just like us.Nonetheless, wherever the biblical teaching has gone, even though it has always been marred by men, it not only has told of an open approach to God through the work of Christ, but also has brought peripheral results in society, including political institutions. Secondary results are produced by the preaching of the gospel in both the arts and political affairs.

What does Schaeffer point to as the beginnings of our own constitutional system?

And where, as in England, Presbyterianism as such did not triumph, its political ideas were communicated through the many complex groups which made up the Puritan element in English public life and played a creative role in trimming the power of the English kings. As a result, the ordinary citizen discovered a freedom from arbitrary governmental power in an age when in other countries the advance toward absolutist political options was restricting liberty of expression.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 137).

Samuel Rutherford’s work and the tradition it embodied had a great influence on the United States Constitution, even though modern Anglo-Saxons have largely forgotten him. This influence was mediated through two sources. The first was John Witherspoon (1723–1794), a Presbyterian who followed Samuel Rutherford’s Lex Rex directly and brought its principles to bear on the writing of the Constitution and the laying down of forms and freedoms.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 138).

Will these ideas work without a Christian grounding? Had they been tried before? [Form (Roman Republic) & Freedom (Greek democracy)]

The second mediator of Rutherford’s influence was John Locke (1632–1704), who, though secularizing the Presbyterian tradition, nevertheless drew heavily from it. He stressed inalienable rights, government by consent, separation of powers, and the right of revolution. But the biblical base for these is discovered in Rutherford’s work. Without this biblical background, the whole system would be without a foundation. This is seen by the fact that Locke’s own work has an inherent contradiction.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 138).

What was the inherent contradiction with Locke? [empiricism vs. natural rights (innate, not through experience)]

To whatever degree a society allows the teaching of the Bible to bring forth its natural conclusions, it is able to have form and freedom in society and government.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 139).

Schaeffer points to the solution to the problem of minority oppression (freedom of speech and though silenced by the intolerant majority) and majority oppression (freedom of speech and thought silenced by the intolerant minority seeking über rights through special interest groups) that innately results in a society one way or another.

So, to the extent to which the biblical teaching is practiced, one can control the despotism of the majority vote or the despotism of one person or group.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 139).

The ideas upon which the Reformation was based were suspicious of human authority.

For this reason, Calvin himself in Geneva did not have the authority often attributed to him. As we have seen, Calvin had been greatly influenced by the thinking of Bucer in regard to these things. In contrast to a formalized or institutional authority, Calvin’s influence was moral and informal. This was so not only in political matters (in which historians recognize that Calvin had little or no direct say), but also in church affairs. For example, he preferred to have the Lord’s Supper given weekly, but he allowed the will of the majority of the pastors in Geneva to prevail. Thus the Lord’s Supper was celebrated only once every three months.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 140).

Did that surprise you about Calvin? Is that what you normally hear in the popular view of him?

Schaeffer pointed to inconsistencies that developed. What were they? (Race, and non-compassionate use of wealth)

Race: the church had much greater influence then than now, yet failed to speak out against it sufficiently.

What “fiction” accounted for this? In what was it based?

Actually they harked back to Aristotle’s definition of a slave as a living tool and were far removed from the biblical teaching.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 141).

What does he point to as the example of the abuse of wealth created by the industrial revolution?

Does his discussion on how the English government approached the Irish potato famine cause you pause in our dealings with certain social justice issues?

A tragic example of the acceptance of these views was the attitude toward the Irish potato famine held by Charles Edward Trevelyan (1807–1886), who was in charge of government relief in Ireland. He withheld government assistance from the Irish on the grounds that they should help themselves and that to do otherwise would encourage them to be lazy. It was not that he lacked compassion or a social conscience (his later career shows otherwise), but that at a crucial point a sub-Christian prejudice stifled the teaching of Christ and the Bible, and sealed Ireland’s doom.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 143).

On slavery in the United States:

To keep the matter in balance: in the first place it must be said that many non-Christian influences were also at work in the culture. Likewise, many influential people who automatically called themselves Christians were not Christian at all; it was merely socially acceptable to bear the name and go through the outward forms. In the second place, many Christians did take a vital and vocal lead in the fight against these abuses. Many Christians struggled to bring into being the social realities that should accompany a Christian consensus. Pastors and others spoke out as prophets, often at great personal cost to themselves. The Bible makes plain that there should be effects in society from the preaching of the gospel, and voices were raised to emphasize this fact and lives were given to illustrate it.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, pp. 143–144).

In the United States some groups did speak out. The Reformed Presbyterian Church in the United States decreed as a denomination as early as 1800 that no slave holder should be retained in their communion, and after that date no slave holder was admitted.

Schaeffer, F. A. (1982). The complete works of Francis A. Schaeffer: a Christian worldview (Vol. 5, p. 145).

It is important to realize that these blights on our history were the result of those acting inconsistently with biblical Christianity rather than because of biblical Christianity.

Leave a Reply